Welcome to the 24th Cable, our weekly roundup of British foreign and defence policy.

What will 2025 have in store for Britain’s interests and position in the world? Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the conflict in the Middle East continue with both likely to evolve in unpredictable ways over the coming months. The era of piped Russian gas to Europe has ended, following the expiration of a five-year deal between Russia and Ukraine. Meanwhile, we are three weeks away from the return of Donald Trump, President-elect of the United States (US). And a number of close allies and partners – from France to Germany, and on to South Korea – lack cohesive governments. 2025 looks set to be an interesting year.

In 2025, the Cable will change. In previous editions, we included a section called ‘Poseidon’, charting the Royal Navy’s weekly deployments. Given the establishment of the Sea Power Laboratory at the Council on Geostrategy and our growing focus on maritime affairs, we are delighted to announce a new monthly newsletter – Poseidon – on Britain’s World to focus on naval strategy and maritime security. We will publish the first edition on Thursday, 9th January. In its place in The Cable, we will include a new section called ‘Kratos’ – named after the Greek god of power – focusing on how Britain’s power and position is changing in the world. From now on, this will alternate with Leckie, our fortnightly overview of how Britain thinks about geopolitical issues.

We look forward to keeping you abreast of the latest geopolitical developments. Welcome back to the Cable!

A year of reviews

In the coming months, His Majesty’s (HM) Government will publish several foreign policy and defence reviews, set to shape Britain’s security and diplomatic posture for the coming parliament. This flurry of activity will provide the best means by which to understand HM Government’s outlook and objectives on the world stage.

Announced in July 2024, the Strategic Defence Review (SDR) – the third strategic review in five years – following the Integrated Review and its ‘refresh’ and two Defence Command Papers – is the cornerstone of Labour’s defence policy. In the deteriorating geopolitical environment, the SDR is to be a ‘root and stem’ overhaul of the UK defence sector focusing on: The strategic and operational context for Britain, force structure and modernisation, international alliances and partnerships, procurement, retention and recruitment, and the defence-industrial base. The SDR is expected to be published in early 2025 alongside a defence industrial strategy and a pathway to spending 2.5% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on defence in the upcoming Spending Review.

In September 2024, David Lammy, Foreign Secretary, announced that the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) would undertake three strategic reviews to enhance Britain’s international position. These reviews focus on various streams of the UK’s foreign policy, investigating the following areas:

Britain’s global impact and how to enhance relationships with international partners;

How to improve the FCDO’s capabilities to evaluate and respond to geopolitical challenges and opportunities;

How to modernise Britain’s diplomatic and development expertise to better fit the changing international environment;

How to place economic growth at the heart of the UK’s foreign policy.

In the press release from September, the reviews were set to conclude by the end of 2024, with additional work to take place in early 2025. However, at the time of writing, there have been no further updates on the review process.

Finally, Labour promised an audit of relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in its manifesto, to provide ‘a long-term strategic approach to UK-China relations.’ However, the release of the audit has now been delayed until after the visit of Rachel Reeves, Chancellor of the Exchequer, to Beijing later this month, where she is expected to revive the Economic and Financial Dialogue with the PRC – part of HM Treasury’s attempt to accelerate economic growth. However, it should be noted that the PRC is not the economic gangbuster it once was, and therefore the potential benefits for Britain-Chinese cooperation are becoming more limited.

Some experts believe that this delay, and the softening of rhetoric towards the PRC, will result in a lacklustre audit, only part of which may now be publicly available. It appears as though HM Government’s ‘3 Cs’ (compete, challenge, cooperate) approach to Beijing will focus more on cooperation, despite the acute threats emanating from the East Asian country.

Key diplomacy

In recent weeks, HM Government has reaffirmed its ‘ironclad’ support for Ukraine, with John Healey, Secretary of State for Defence, announcing a new £225 million military package, during his visit to Kyiv on 19th December. Likewise, on 23rd December, HM Government declared it would provide £4.5 million to support Kyiv’s efforts to hold Russia accountable for the war crimes its forces have committed during the invasion of Ukraine. These packages are in addition to Britain’s annual commitment of £3 billion in military aid and a £2.26 billion loan agreed last year.

At the United Nations (UN) Security Council, British diplomats issued two statements focused on aggressors:

On 23rd December, Fergus Eckersley, Minister Counsellor at the UN Security Council, launched a rebuke against Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, stating that: ‘Until Russia ceases aggression, we [the UK] will continue to support Ukraine in defending itself’;

On 30th December, Barbara Woodward, Permanent Representative to the UN, condemned the ongoing Houthi missile and drone attacks against Israel and the targeting of international shipping in the Red Sea. Woodward concluded by stating that Britain supports deescalation in the region and raised concerns over Israeli attacks against Yemeni civilian infrastructure.

Last week, Reeves responded to a question raised by the International Development Committee in the House of Commons, asking when the UK will return to the 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) target for overseas aid. Reeves stated that HM Government is committed to returning to the 0.7% target when ‘fiscal circumstances allow’, though did not explain when this would be. On 7th January, Anneliese Dodds, Minister for Development, will give evidence to the International Development Committee on the Government’s approach to aid spending.

Britain has announced a £61 million aid package to regions facing humanitarian crisis and conflict. The extra aid is part of HM Government’s Plan for Change initiative, which aims to ‘tackle migrant flows upstream’ by addressing climate impacts and global poverty. The breakdown of this new aid package includes:

£22m to the Middle East to respond to the escalating crisis in the region;

Up to £18 million to countries in the Sahel, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Somalia;

Up to £16 million to Myanmar and Bangladesh;

£5 million to respond to the impacts of Cyclone Chido in Mozambique.

Defence

The Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) – a UK-led minilateral defence coalition – activated an ‘advanced reaction system’ to track potential threats to undersea infrastructure and to monitor Russia’s shadow fleet. Operation NORDIC WARDEN will harness Artificial Intelligence (AI), alongside other information gathering techniques, to assess data from ships to calculate the threat level they pose across Northern Europe. The decision to activate the reaction system follows several events that have damaged European critical undersea infrastructure in recent months, most recently three cables linking Finland and Estonia and a fourth linking Finland and Germany were cut on Christmas Day by a suspected ship in the Russian shadow fleet.

The Ministry of Defence (MOD) has signed a seven-year contract for £476 million with Foreland Shipping Limited to provide ‘Global Strategic Sealift’ capabilities to the British Armed Forces. Foreland Shipping Limited will provide ‘four roll-on roll-off shipping vessels capable of transporting essential equipment and supplies…emergency medical supplies and complex weapons, across the globe.’ Such capabilities are key for Britain to project power and support allied forces.

The MOD has signed a £1 billion deal with six construction companies to improve accommodation across the Defence Estate. The new accommodation is expected to improve quality of life for service personnel and, alongside the buy back of 36,347 military homes announced in December, is part of the MOD’s strategy to modernise the Defence Estate, save money and improve personnel retention in the armed forces.

The Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) has developed a ‘groundbreaking’ atomic clock using quantum technology which will offer improved intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. While an exceedingly accurate clock may not sound all that exciting, the technology will enable precise and independent navigation systems, more secure communication systems, improve the accuracy of guided weaponry, and provide an edge in the cyber domain. According to DSTL, the technology will be in operational use by 2030.

Environment and climate

Britain’s electricity mix was the cleanest ever recorded in 2024, with the carbon intensity per kilowatt hour (kWh) falling two thirds in the last decade from an average of 419 grams of CO2 in 2014 to 124 grams of CO2 last year. According to analysis by Carbon Brief, the UK has seen a 55% reduction in fossil fuel generation since 2014, with renewable energy more than doubling over the same period. Overall, this has resulted in a 74% decline in electricity related emissions in the UK over the last decade.

How Britain is seen overseas

In recent weeks, Elon Musk, CEO of Space X, Tesla and X, has developed a peculiar interest in British politics, most recently taking to X to attack HM Government’s handling of the grooming gangs scandal. Musk, who has been increasingly focused on British politics since the riots last summer, has also called for the release of Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, jailed for contempt of court, and been repeatedly critical of the Labour government.

It remains to be seen what impact the continuing ire of the world’s richest man, who is also a central figure in the incoming Trump administration will have. The key question going forward is whether his views are shared by Trump and, if so, how Sir Keir Starmer, Prime Minister, will respond.

How competitors frame Britain

Sputnik International released propaganda stating that the British Armed Forces are falling behind their competitors. The piece states that this underinvestment has resulted in the British Army shrinking in size and an aging submarine fleet. An interesting take from Russian state news considering the Russian military is using 60-year-old tanks in Ukraine.

Russia Today cited a report by The Times that Britain is vulnerable to missile attacks and that North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) allies are frustrated with British air defence capabilities. The article concludes with a warning from Vladimir Putin, President of Russia, that Moscow ‘reserves the right’ to use its weapons against countries that have given Ukraine permission to use long-range missiles on Russian territory. Mere bluff from a country which has failed to seize a far less powerful nation.

Assessing national power

What countries are the world’s most powerful? Many strategists ask this question as it helps when creating policy. If another country is becoming too strong, others may seek to bandwagon with it or degrade its power. If a rival power is weakening, others may attempt to shore it up or take advantage of its plight. Over the past decade, there has been a pervasive fear that the so-called BRICs countries – the PRC, India, Russia and Brazil – are overtaking the established democracies, such as the UK.

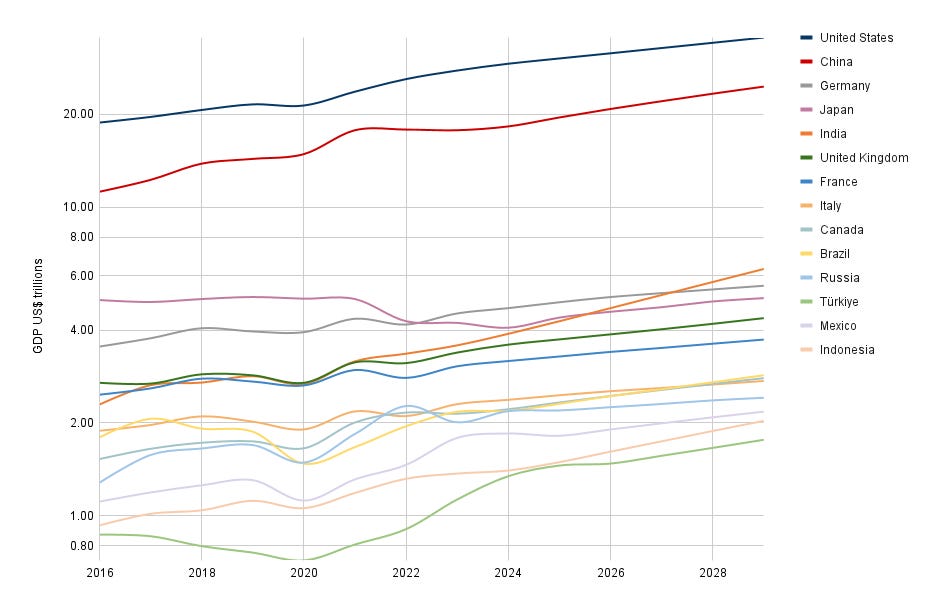

Unfortunately, there is no satisfactory method for measuring national power. It is often unclear what is even meant by power: it can be defined as a capability, a relationship, or an outcome. Strategists often use Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a proxy to measure capability; if looked at in this way – as the graph below shows – the BRICs appear to be gaining on the established democracies.

But using GDP as a proxy for national power suffers from severe limitations: it accounts for gross and not net power. In other words, it does not take into account national costs and liabilities, nor technological or organisational strength. For example, in terms of GDP, the PRC has surged ahead of many countries in recent years, but does that mean it is more powerful? The Chinese economy may now be significantly larger than Britain’s, but Beijing has to feed, cloth and house 1.35 billion more people, before it can use its economic yield to secure its global interests. Of course, a government can ignore the needs of its people, but only for so long – as the Soviet regime eventually found out.

Other systems have been developed – such as the Composite Index of National Capability, the Asia Power Index, and many others – but these suffer from their own problems. They either see total resources as paramount or their methodologies overemphasise proxies for technological and organisational strength, leading to peculiar results. In the Asia Power Index, for example, Singapore, a city state of a mere 5.9 million people, ends up with a score of 26.4, versus 81.7 for the US. This means that the American superpower is only three times stronger than Singapore – hardly a serious proposition.

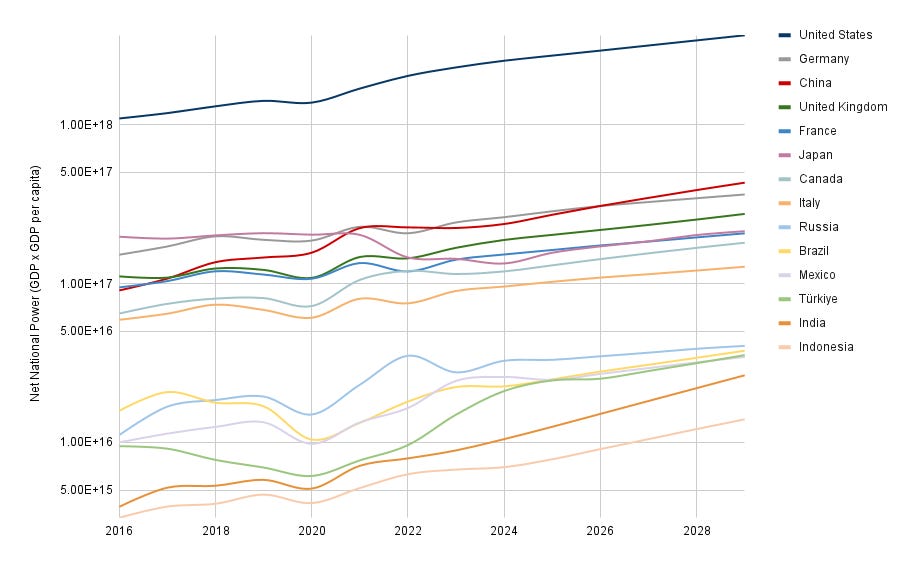

One academic, Michael Beckley, thinks the answer lies in focusing on measuring net power. His solution involves a simple calculation which multiplies GDP by GDP per capita – with the former representing a country’s total economic capacity and the latter signifying – roughly – its technological and organisational strength. Save for a few small tax havens and petro-states, there is certainly a strong correlation between a high GDP per capita and national development.

Though not perfect, Beckley’s approach attempts to strike a better balance between the resources available to a country and its technological and organisational capability. As the graph above shows, when looked at through this lens, the US retains its commanding lead over the PRC, just as the other Group of Seven (G7) countries retain a potent edge over Russia, Brazil and India. And while ranking sixth in terms of GDP in 2025, the UK ranks fourth in terms of net national power. There may well be life in the old democracies yet.

The analysis in this section is based on work the Council on Geostrategy completed for the Secretary of State’s Office of Net Assessment and Challenge in the Ministry of Defence between 2023 and 2024.

If you found this Cable useful, please subscribe or pledge your support!

What do you think about this Cable? Why not leave a comment below?

This retained reliance on GDP or GDP per capita is silly. The qualitative composition of an economy (e.g., what contributes do a given GDP) is extremely important in evaluating any sort of power projection abilities. For instance, an economy largely based on services will not be able to muster the same military capacity as an equally large economy with a strong heavy industry sector.

Hence it doesn't really make sense to say the UK or France (let alone Italy) are ALONE possess a greater 'national power' than Russia even if they have larger economies in quantitative terms. It is obviously true that Russia has a greater *industrial capacity* as is needed in times of war, whereas the UK would have more difficulty transitioning into a war economy. Plus, a lot of the UK economy, especially in terms of defence, is integrated in and dominated by the US, taking away from its strategic autonomy and ability to act in a truly sovereign manner. By contrast, Russia has been 'sanctions proofing' its economy and bolstering its own 'independent' industrial capacity since the 2008 Georgia War. Thus, the UK's (and all of Europe's) power is heavily limited by what the Americans want. We could not conduct a serious military operation without American support. Even during the Libya campaign the UK and France were running out of munitions, and that was just an air war.

On top of that, in military terms this downplays the factor of manpower. If the Russian invasion of Ukraine has shown anything, it's that modern peer-to-peer warfare among technologically advanced militaries is very attritional and has a strong defender bias. The days of grand manoeuvres a la Blitzkrieg are gone. Even w/ the significant advantages Russia has over Ukraine it has been making progress very slowly-but its overall advantage has come from the overall quantity of soldiers (whereas Ukraine has had to resort to unpopular and poorly conducted conscription that has resulted in a massively lowered infantry quality) and quantity of equipment, even if it's older than what the west has.

The west, especially the UK and Europe, has a far smaller stock to rely on which would run out quickly in a war with anyone serious (e.g., not against a withered Iraqi Army or a weak Taliban, neither of whom could contest air control).

If it is even possible to quantify 'national power' (I think it is possible in a crude sense, though you'd still need a far more complex calculation than anything you've suggested here!) then simply realities on the ground clearly show that Russia, for all the aspects in which it is declining, retains an individually greater power projection ability than anyone bar the US and China.