From 14th September to 1st October, aircraft of the Japan Air Self-Defence Force (JASDF), alongside 180 personnel, were stationed at RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire. The mission, named ATLANTIC EAGLE, marks the JASDF’s first European deployment in its 71-year history, and highlights the growing strategic partnership between the United Kingdom (UK) and Japan.

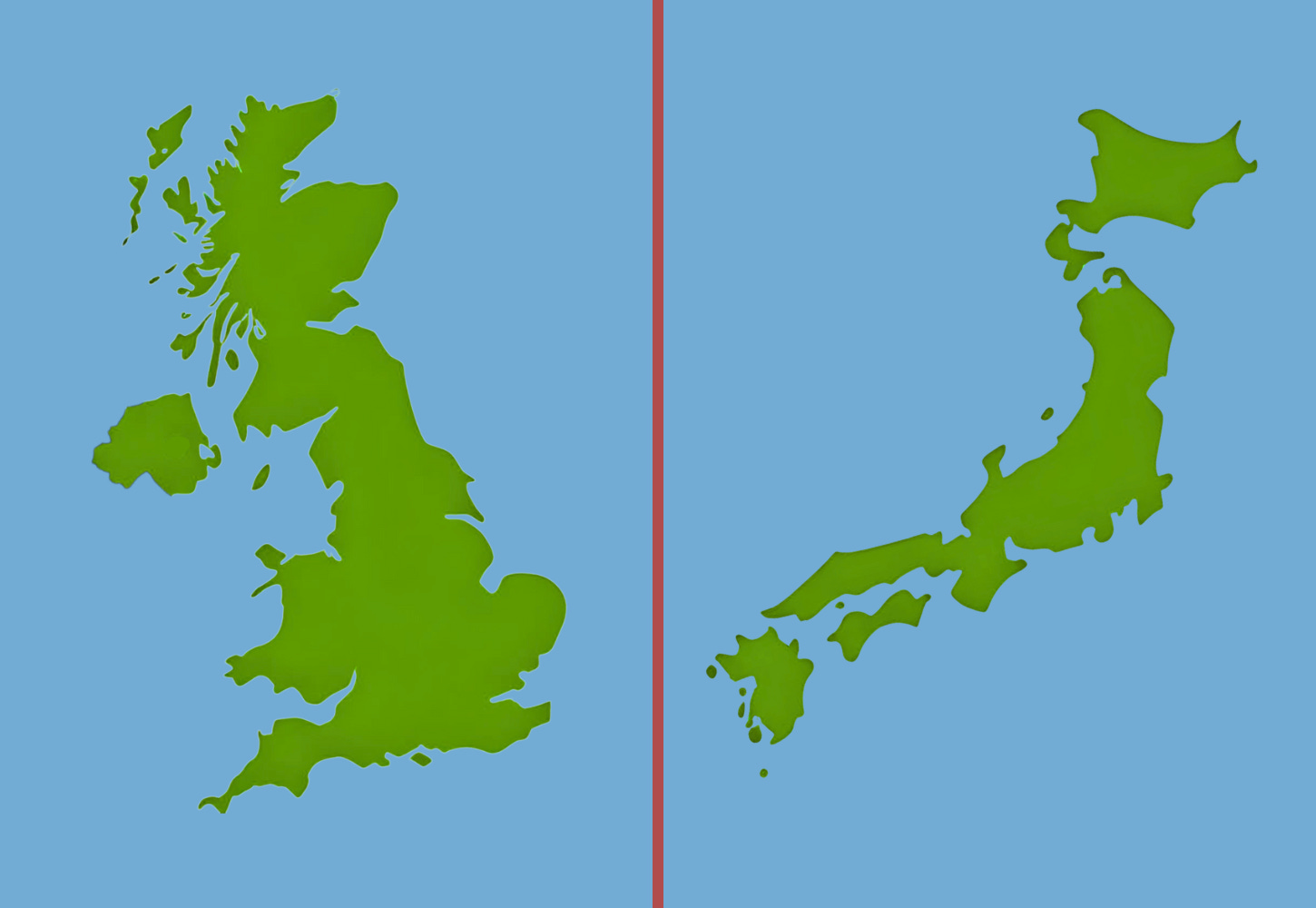

As well as ATLANTIC EAGLE, both nations are spearheading Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific connectivities through initiatives such as the Global Combat Aircraft Programme (GCAP), the Carrier Strike Group 2025 (CSG2025) visit to Tokyo, the Hiroshima Accord strategic partnership and the Reciprocal Access and Cooperation Agreement. As a next logical step for this bilateral relationship, for this week’s Big Ask, we asked seven experts: Should Britain and Japan move towards a formal defence alliance?

Deputy Director (Geopolitics), Council on Geostrategy

While it would have seemed almost impossible to consider Japan formally allying itself with another country only a few years ago, the fact is that relations between the United States (US) and Japan – and perceptions of a lack of American reliability – have hit Japanese policy elites hard. While many still adhere to the day-to-day primacy of the relationship through all the various bilateral institutions and working groups, there is, at the political level, a growing dissatisfaction with Washington’s tariffs and escalating demands for higher defence spending.

The arrival of HMS Prince of Wales, one of the Royal Navy’s aircraft carriers, into Tokyo Bay in August was only the most recent highlight in a long-growing bilateral defence relationship which includes major defence industrial programmes such as GCAP and the Joint New Air-to-Air Missile (JNAAM).

Alongside Australia, the UK has become Japan’s premier non-US security partner of choice. Based on a series of agreements on arms transfers, military information sharing, logistics agreements and the Hiroshima Accord, the two countries already have a very alliance-like relationship.

However, the ‘meat and potatoes’ of an alliance is not security cooperation, but one-way or mutual defence obligations. Such commitments can be made expressly through a treaty, or informally.

Would Britain and Japan be willing to defend each other if the one was attacked? There is a huge gap in public support in both countries for such a contingency, though perhaps there is an argument to be made.

There is a growing perception among policymakers in both London and Tokyo that Vladimir Putin, President of Russia, and Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are ever more aligned, that what occurs in one theatre affects the other, and that deterrence opportunism is a joint activity.

So, in the end, the answer to the question is yes-ish. The two nations should move in that direction and pave the way for a formal alliance, should time require it.

Takeshi Ishikawa

Former Commissioner, ATLA, Ministry of Defence of Japan

Nowadays this topic is discussed from time to time, but it is useful to look back at history before discussing it.

In 1902, although only 35 years had passed since Japan ended three centuries of isolation with the Meiji Restoration, renovating its domestic political system and opening the door to trade with a rich country, it formed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance with the UK – one of the strongest countries in Europe and a practitioner of ‘splendid isolation’.

This alliance was formed by two island countries located to the east and west of the Eurasian continent – both facing tsarist Russia’s southward advance – to pursue their common security interest. It was the first equal military alliance between a European and an Asian country, and greatly surprised the international community at the time. The alliance stipulated that if one party was attacked, both would jointly defend it. And it was not temporary; lasting over 20 years until 1923.

Although Britain was officially neutral in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, in reality, it supported Japan in various ways, including through intelligence, naval sabotage and war financing. Japan entered the First World War in 1914 on the side of Allies, based on the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, dispatching eight destroyers to the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea to escort Allied transport ships during 1917-1918.

Thus, at the beginning of the 20th century, the alliance between the UK and Japan significantly achieved the effect of mutually satisfying their respective strategic interests in the great power competition of the period.

Now, in the 21st century, over 100 years after the alliance, Britain and Japan are working together to address common challenges in security and defence, based on the US-Japan alliance and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). The latest international security environment is clearly intricately different from a century ago.

Both countries’ challenges are increasingly common and obscure, such as addressing sub-threshold conflict. In order for the UK and Japan to work together most effectively to deal with them, they should think really innovatively again about what kind of strategic partnership they should build.

Assistant Professor, Strategic Studies, Nanyang Technological University (NTU) Singapore

Diplomacy, like politics, is the art of the possible. Negotiating a formal treaty would be time-consuming and raise thorny questions – what, for example, would Britain do if war broke out in East Asia, and how might Japan respond to an attack on NATO?

Such commitments would need to be defended to domestic audiences. It is unclear whether either government is prepared to expend the necessary political capital, given the challenges both face at home. Nor are formal treaties a panacea for reassurance. Even NATO’s Article Five, often upheld as the gold standard of collective defence, does not guarantee a robust response.

The UK-Japan partnership should instead be celebrated for what it is: an emerging entente. The 2010s saw a quickening drumbeat of ministerial dialogues and military exercises, as both sought mutual reassurance amid deteriorating security environments. Both are key US allies, watching the trajectory of American grand strategy with some concern. Thus, a strong partnership between these maritime, second-tier powers makes eminently good sense.

Through the 2023 Hiroshima Accord, both countries pledged ‘to consult’ on global and regional security challenges, while defence-industrial ties are blossoming through GCAP. Most recently, the high-level ministerial turnout for CSG2025’s visit to Tokyo illustrates the weight accorded to the relationship within both governments.

True, ententes cannot resolve the reassurance dilemma, but their intrinsic ambiguity can itself be a deterrent, complicating the calculations of potential aggressors. Rather than engaging in lengthy treaty negotiations, Britain and Japan should focus on tangible outcomes, such as delivering GCAP on time.

Lecturer in Defence Studies, UK Defence Academy, King’s College London

In January 2023, Rishi Sunak, then Prime Minister, declared ‘the next chapter’ in UK-Japan relations. Hosting Fumio Kishida, then Prime Minister of Japan, at the Tower of London, Sunak argued that Britain and Japan ‘shared so much in common’, with a ‘shared outlook on the world’ and ‘a shared understanding of the threats and challenges’.

Action has followed rhetoric. Whether through the respective visits of Carrier Strike Groups 2021 and 2025 to Japan, RAF participation in Exercise MOBILITY GUARDIAN, or the British Army through Exercise VIGILANT ISLES, there is a clear uptick in both the scope and scale of British-Japanese military cooperation. The centrepiece of this was the 2023 Reciprocal Access Agreement, characterised as the ‘most important defence treaty between the UK and Japan since 1902.’

Yet, this is not 1902. The world is a very different place today, as are Britain and Japan’s positions within it. While the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has greatly reduced the distance in both nations’ approach to Russia, the question of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) remains a thorny issue.

Britain continues to balance economic interests and strategic concern, while Japan gauges immediate territorial disruptions with regional ordering. Both nations share common concerns – such as international stability and an increasingly erratic partner in the US, to name two – but the necessary shared threat perception which solidifies formal alliances remains lacking.

Geography, threat perception and strategic culture all ensure that a ‘formal’ alliance remains a distant ideal. Both nations should continue to foster growing links at the political and official level, developing a greater understanding of each other’s practices and concerns to build upon for the future.

PhD Student, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University

A formal alliance entails reciprocal defence obligations and legal enforceability, which makes a UK-Japan treaty difficult for now. Yet, to signal resolve credibly across the Indo-Pacific, and to bolster deterrence against coercive revisionism, deepening British-Japanese security ties is indispensable.

London and Tokyo have already made major strides with GCAP, the Hiroshima Accord, the Reciprocal Access Agreement, CSG2025’s visit to Tokyo and the ATLANTIC EAGLE deployment. These steps have turned the bilateral relationship into a genuine strategic partnership.

Gaps remain in several operationally decisive domains: joint munitions production and stockpile sharing; integrated Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) and layered Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD); persistent Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) and cyber/space cooperation; pre-agreed crisis access, rules of engagement and legal frameworks; and coordinated economic-security measures, such as sanctions, export controls and Sea Lines of Communication (SLOC) protection. Left unaddressed, these limits blunt the credibility of any bilateral deterrent.

A prudent path is a modular, pre-alliance architecture: rapidly declarable contingency assistance packages; bilateral logistics, maintenance and munitions compacts; standing combined ISR, ASW and IAMD task groups; pre-set sanctions triggers; and routine, visible British force rotations. This layered approach maximises deterrence, preserves national discretion and keeps the option of a formal alliance open should strategic circumstances require it.

Senior Research Fellow, Indo-Pacific Security, RUSI

Over more than a decade of diligent diplomacy and commitment to defence cooperation across all the services and domains since 2012, Britain and Japan have eased quietly into a de facto defence alliance, based on an aligned strategic outlook, co-dependency in critical areas of the defence industry, and converging interests in economic security (including sensitive capabilities such as cyber).

‘Japan is the UK’s closest security ally in Asia, and I know Japan sees Britain as its closest security partner in Europe’, remarked John Healey, Secretary of State for Defence, to an audience assembled on board HMS Prince of Wales in Tokyo this summer. Japan’s use of ‘partner’ – not ‘ally’ – stems from diplomatic consideration for its sole treaty ally (the US), legal conditions limiting its freedom to commit to collective defence, and divided public opinion.

A peacetime partnership was appropriate for the world of 2012. Today, Russia is three years into a full-blown conflict in Europe, supported by Beijing and Pyongyang. The US is set to prioritise defence of the western hemisphere over power projection in Asia. The quality of trust London and Tokyo have built over the intervening period is at a premium, yet it is under-leveraged.

If Shigeru Ishiba, the soon-to-depart Prime Minister of Japan, was correct when he said ‘today’s Ukraine could be East Asia tomorrow’, it matters less what term is used to describe the relationship, and more that it is reframed with the explicit goal of deterrence. Sir Keir Starmer, Prime Minister of the UK, should work with Ishiba’s successor to maintain progress on capability development, but also push interoperability to the forefront, increasing the frequency and scale of exercises which signal readiness to unite under wartime conditions.

Professor, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University, and Deputy Director, Keio Centre for Strategy (KCS)

Should Britain and Japan move towards a formal defence alliance?

Not quite. The idea of forging a formal defence alliance between the UK and Japan, in which the two countries commit to defend each other against aggression, cannot be credible, not least because they lack necessary military capabilities. Additionally, any effort made towards this purpose will cause unnecessary and unhelpful political debates in both countries – particularly in Japan, where the very idea of the right to collective self-defence remains highly controversial.

Yet, it is not actually bad news for British-Japanese security and defence cooperation, because there are so many areas which they could pursue without having a legally binding security treaty. The absence of a mutual defence commitment should not be seen as an obstacle to further cooperation.

The UK and Japan, together with Italy, are co-developing the next generation of fighter aircraft in the context of GCAP, showing enormous potential for defence industrial cooperation between London and Tokyo. In more operational terms, it is notable that the Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force (JMSDF) helped to protect the UK-led CSG2025 during its deployment in the Indo-Pacific.

That said, while still being short of a formal mutual defence commitment, Britain and Japan could consider using the language which Japan and Australia employ. The Japan-Australia Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation of December 2022 stated that ‘We will consult each other on contingencies that may affect our sovereignty and regional security interests, and consider measures in response.’ There is no reason this is not possible between London and Tokyo.

If you enjoyed this Big Ask, please subscribe or pledge your support!

What do you think about the perspectives put forward in this Big Ask? Why not leave a comment below?

Dude not again!!!

https://open.substack.com/pub/thebluearmchair/p/slouching-towards-bethlehem?r=5kmhkr&utm_medium=ios