Welcome to the 11th Cable, our weekly roundup of British foreign and defence policy. The Cable is published every Tuesday.

In his first major speech at Kew Gardens, David Lammy, Foreign Secretary, stated his intention to put climate action at the heart of British foreign policy. Highlighting the links between climate change, geopolitics and global instability, Lammy warned that ‘[while] the threat may not feel as urgent as a terrorist or an imperialist autocrat. It is more fundamental. It is systemic. It is pervasive. And it is accelerating towards us at pace.’

Lammy stated that His Majesty’s (HM) Government aims to be a global leader on tackling environmental degradation and announced several new actions to further this goal: firstly, HM Government will create two new special representatives for climate and nature to provide advice and support; secondly, HM Government will establish a global clean power alliance, to share British expertise and experience with other countries, particularly in the developing world. And finally, the United Kingdom (UK) will strive for more climate finance to be made available internationally.

Key diplomacy

Sir Keir Starmer, Prime Minister, travelled to Rome on 16th September for talks with Giorgia Meloni, his Italian counterpart – part of his planned ‘reset’ of relations with the UK’s close European allies. Both leaders agreed to strengthen British-Italian partnerships across key areas including defence, irregular migration and trade – the meeting concluded with the announcement of £485 million investment into Britain from Italian companies.

The UK and Indonesia agreed to strengthen cooperation on climate mitigation and development. Anneliese Dodds, Minister of State for Development, as well as Women and Equalities, participated in a three-day visit to the southeast Asian country (16th-19th September), where she signed a Memorandum of Understanding to enhance development cooperation to help Indonesia’s energy transition and create a strategic partnership on critical minerals.

Lord Coaker, Minister of State, visited the Republic of Korea and Vietnam to enhance the UK’s commitment to Indo-Pacific security:

In Seoul, Lord Coaker attended the Responsible Artificial Intelligence in the Military (REAIM) Summit, which focused on the uses for and the risks of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the military. He also met Seon ho Kim, Vice Defence Minister, to discuss Britain’s defence partnerships with South Korea.

In Vietnam, Lord Coaker co-chaired the fifth Annual UK-Vietnam Defence Policy Dialogue; he also held discussions with senior Vietnamese officials to strengthen the defence relationship between the two countries.

Defence

Britain, the United States (US) and Canada will collaborate on cybersecurity and Artificial Intelligence (AI) research. This decision has been driven by the rapid pace of technological development and the worsening geopolitical environment. The agreement will streamline technological development by reducing duplication and pooling resources, so that new capabilities can be operationalised as quickly as possible.

The Ministry of Defence (MOD) has signed a £71 million contract to maintain thousands of British Armed Forces land vehicles. This will see maintenance of over 15,000 vehicles for the next four years be placed under a single contract, consolidating and simplifying the maintenance of the vehicle fleet.

John Healey, Defence Secretary, has announced several reforms to tackle the long-standing recruitment challenges the British Armed Forces face. At the Labour Party Conference, Healey revealed several of these reforms to improve recruitment: 1. Scrapping ‘outdated’ policies that currently block people from joining the military; 2. Accelerating and streamlining the application process; and, 3. Introducing a direct recruitment route for cyber specialists, particularly coders and gamers.

How Britain is seen overseas

The Council on Foreign Relations in New York released a short commentary article which critiqued Lammy’s maiden speech at Kew Gardens. The piece argues that, due to a major land war in Europe, Iran developing nuclear weapons, and the war in the Middle East, the Foreign Secretary should focus on these destabilising events rather than climate change. The article also critiques Lammy for underplaying the growing global disorder and the profound threat Britain and other free and open nations face from terrorism and revisionist powers.

How competitors frame Britain

Sputnik International released propaganda claiming that Britain’s economic outlook has been worsened by a ‘political class’s readiness to sacrifice the economic interests of ordinary Britons in favour of foreign [Ukrainian] elites.’ The article states that several factors including sanctions on Russia, support for Ukraine and economic decoupling from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have caused the UK’s debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio to reach 100%. Is it not ironic that Russia is talking about unsustainable economic policy, when it has committed its own people to penury by launching a costly war?

An editorial by the Global Times called for an end of the era of poor London-Beijing relations and a move towards a mutually beneficial relationship for both countries. The Chinese state outlet calls on Britain to move away from the three Cs of compete, challenge and cooperate to the ‘better new Cs’ of communication, consensus, and cooperation. Of course, the Global Times mentions nothing of the PRC’s aggressive revisionist posture in undermining British-Chinese relations.

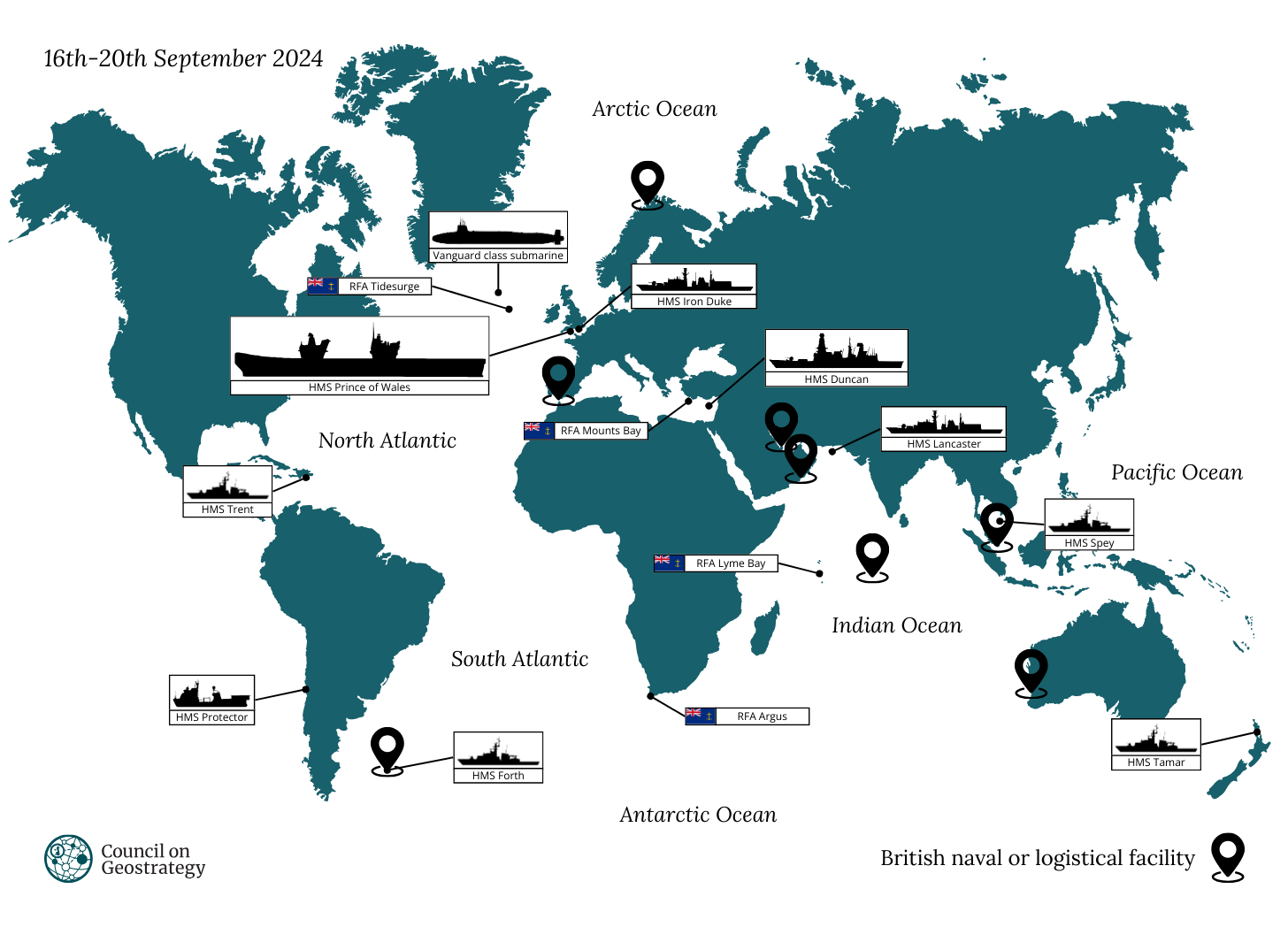

Tracking the Royal Navy’s global deployments

16th-20th September: Though invisible, the Royal Navy’s ballistic missile nuclear submarine was deterring the gravest threats to British interests from the depths of the North Atlantic last week. Supercarrier HMS Prince of Wales spent time exercising in the English Channel. HMS Iron Duke shadowed Russian warships in the English Channel, while HMS Duncan remained present in Cyprus. On the other side of the world, HMS Protector remained in Chile, while HMS Lancaster conducted a passing exercise with a Pakistani warship in the Arabian Sea.

Offshore patrol vessels HMS Forth, HMS Trent, HMS Spey and HMS Tamar continued to maintain a British presence across the globe. HMS Forth remained on station in the Falkland Islands, HMS Trent visited Puerto Rico, HMS Spey left the British logistics facility in Singapore en-route to Cambodia, and HMS Tamar remained in New Zealand.

The Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) was also present in many locations: RFA Argus visited South Africa, RFA Lyme Bay visited the Maldives, RFA Mounts Bay arrived in Rhodes in Greece, and RFA Tidesurge was in the North Atlantic.

How Britain thinks about foreign affairs

Over the past few weeks, Ukraine’s plight has become apparent. Despite the ongoing Ukrainian push into Kursk – which crossed yet another of the Kremlin’s ‘red lines’ – Russia’s war against Ukraine grinds on with no sign of a breakthrough on either side in sight.

The UK has been at the forefront of efforts to convince its allies and partners to provide Ukraine with more assistance. It has gifted to Kyiv more material military help than any country other than the US and Germany, and – perhaps more importantly – it has been at the cutting edge in terms of training Ukrainian forces, providing intelligence and military operational assistance, and banging the drum for the Ukrainian cause. It is no surprise that the Ukrainians see in Britain their most powerful and willing European partner.

Implications

At face value, Britain’s position may seem strange. After all, due to their proximity, most large continental countries, not least Germany, would suffer more than Britain should Russia prevail in Ukraine. Germany may have provided more material assistance than Britain, but Berlin has hardly led from the front. France and Italy appear disinterested at best, and distracted at worst.

It would be easy to argue that some of Britain’s stance is because the previous Conservative government wanted to prove the continued existence of British influence after withdrawing from the European Union. But it goes deeper than that.

To begin with, Britain sees Russia as a kleptocratic tellurocracy, utterly antithetical to its liberal thalassocratic self. Further, Britain still thinks like a great power. Two implications follow: first, unlike most other European countries, the UK knows that its nuclear deterrent – Trident – forces Russia to treat it as a peer; second, Britain feels a sense of ownership of the European order, an order it did more than any other country to construct.

This is why, despite several prime ministers, a general election, and a changing domestic political scene, the UK has remained steadfast behind Ukraine. The question is: is Britain prepared to marshal the resources needed for the struggle ahead?

Read more: The trilateral initiative: A minilateral to catalyse Russia’s defeat? – James Rogers and William Freer, 24/09/2024

If you found this Cable useful, please subscribe or pledge your support!

What do you think about this Cable? Why not leave a comment below?