Welcome to the first Cable, our weekly roundup of British foreign and defence policy.

What an important week it has been! The Labour Party won the general election with a thumping majority. After 14 years of Conservative rule, practitioners and analysts are keen to know what the new British government’s foreign and defence policy will look like, not least because, with a large parliamentary majority, the United Kingdom (UK) is in a strong position to shape the world in accordance with its interests.

Since becoming prime minister on Friday morning, Sir Keir Starmer began to make courtesy calls to several foreign leaders. The first calls went to Washington, Kyiv and Brussels, followed by Dublin, Rome, Warsaw, Ottawa, New Delhi, Tokyo, Canberra, Paris and Berlin. The general theme of these calls focused on strengthening British relationships to drive economic growth, maintain support for Ukraine, and tackle climate change, migration and the challenging geopolitical environment.

On entering King Charles Street on Friday afternoon, David Lammy, the new foreign secretary, gave a short speech at the Foreign Office. He promised ‘a gear-shift when it comes to delivering on European security, global security and British growth’, before outlining three key ‘resets’: on Europe, on climate, and in relation to the ‘Global South’ (Labour’s term for the previous government’s concept of the ‘middle ground’). Over the weekend, during a whirlwind trip to Berlin, Warsaw and Stockholm, he wrote a commentary in The Local Europe to declare the new government’s intention to ‘reset’ relations with the European Union (EU) and stress Britain’s ‘ironclad’ commitment to Ukraine and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO).

Meanwhile, John Healey, the new defence secretary, told officials at the Ministry of Defence that the British Armed Forces had been ‘hollowed out and under funded for 14 years.’ In response he declared that he ‘is totally committed to 2.5% of defence spending, to NATO, to the nuclear deterrent and to support for Ukraine.’ He then travelled to Odesa in Ukraine to announce a new package of military assistance, including 100 new Brimstone missiles for the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

What does this mean? It is clear – from the sequence of Starmer’s calls to the first foreign trips of Lammy and Healey – that the geopolitical arc from the Baltic to the Black Sea will be central to the new government’s geopolitical agenda. This dovetails with Labour’s ‘securonomics’ and the Five Missions – economic growth, pursuing green energy, reestablishing law and order, breaking down barriers to opportunity, and reforming the National Health Service – insofar as insecurity in Europe will reduce British prosperity.

The new trio will be busy over the next month: this week, Starmer, Lammy and Healey will travel to Washington for the annual NATO Summit, marking the 75th anniversary of the alliance, while on 18th July, they will host at Blenheim Palace the bi-annual summit of the European Political Community.

How Britain is seen overseas

Over the last two weeks, foreign parliamentary research services, think tanks and universities focused on the British general election may affect their countries and regions.

The Congressional Research Service has produced an ‘Insight’ report to sketch the key issues which may affect British-American partnership under the new government, including policy towards defence spending, Ukraine, AUKUS and the Indo-Pacific, and the UK-United States (US) economic relationship.

The Norwegian Institute of International Affairs asks how the new government will affect British strategy towards Northern Europe, concluding that there will be a great deal more continuity than change – an opinion the Belfer Centre shares in its assessment of Britain’s likely policy towards Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine.

Georgetown University looks at how the Labour Party’s victory will affect relations between the UK and the European Union (EU). It notes they ‘would certainly improve’, but that Starmer will need to ‘tread warily’, insofar as any attempt to get too close to the bloc may generate a ‘noisy domestic distraction from his government’s agenda’.

The Polish Institute of International Affairs asks whether, irrespective of Labour’s intentions, some EU countries – especially France – may continue to drive a hard bargain, while the Council on Foreign Relations concludes that ‘the next British government faces a daunting foreign policy agenda.’ There can be no question there!

Finally, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute has released a report entitled ‘Full tilt: The UK’s defence role in the Pacific’. This urges the new government to ‘promptly and publicly reaffirm the UK’s commitment to a persistent forward defence presence in the Indo-Pacific’, including the Submarine Rotation Force envisaged under the AUKUS agreement.

How competitors frame Britain

Sputnik International carries propaganda claiming that Starmer wants to uphold ‘Western hegemony’ using British nuclear weapons. It seems the publication is unaware that Russia has the world’s largest nuclear stockpile and that the Kremlin is unique in threatening to use it against non-nuclear states.

The Global Times advises the UK to balance collaboration and competition with the PRC for a successful ‘China policy’. It appears the Chinese Communist Party is afraid of losing access to the wealthy British market.

The Global Times also published a cartoon lampooning the speed of prime minister turnover in the UK since 2016. At least Britain has democratic elections, unlike the PRC.

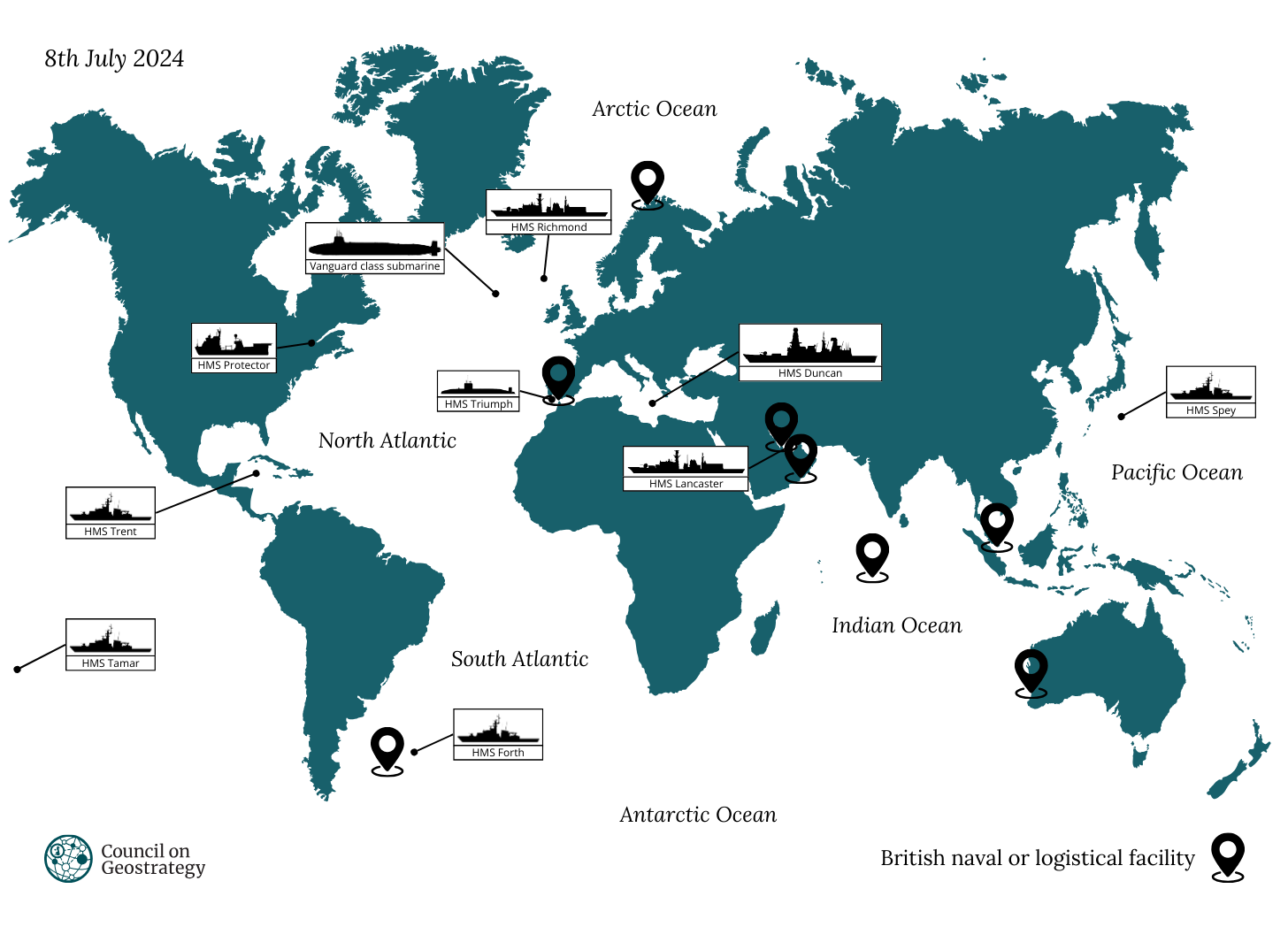

Tracking the Royal Navy’s global deployments

The Royal Navy was engaged around the world during the first week of July 2024, with HMS Forth on patrol around the Falkland Islands, HMS Trent deployed to the Caribbean, HMS Spey is on the high seas having recently completed repairs in Japan, and HMS Tamar is attending Tonga’s Fleet Review having exercised with Australian and Japanese warships off Cairns. HMS Protector is visiting Quebec, HMS Lancaster left Dubai to patrol in the Gulf, and HMS Richmond is monitoring the North Atlantic to protect the nuclear deterrent (comprising a Vanguard class ballistic missile submarine lurking under the North Atlantic). Meanwhile, as HMS Diamond returns home to Portsmouth after a seven-month deployment to counter the Houthis in the Red Sea (sporting a ‘kill count’ of 10 drones and missiles), HMS Duncan exercises as it passes through the Mediterranean to replace her. And HMS Triumph, the Royal Navy’s remaining Trafalgar class nuclear attack submarine, leaves Gibraltar en-route to Plymouth.

How Britain thinks about foreign affairs

Does the new government have a theory of international relations? What is its strategic doctrine? This matters, because how a government thinks about foreign policy affects what it does – and does not do. It is often thought that left-wing governments are more quixotic than their right-wing counterparts; that they bleat about ‘human rights’, foreign aid and international cooperation. But is this always the case?

Ernest Bevin, a former Labour foreign secretary, did not think so. It is because of his advocacy that the Cabinet decided to embrace a British nuclear weapons programme, without which Washington and Moscow would have looked down on London as a secondary power.

We’ve got to have this thing [the atomic bomb] over here, whatever it costs. We’ve got to have the bloody Union Jack on top of it – Bevin, January 1947.

And his decision to embrace a ‘continental commitment’ in 1947 led first to the Western Union and then to NATO, which smothered European geopolitics and laid the foundations for post-war prosperity, including European integration (though he was opposed to British participation). He understood that pursuing power and progress can go hand-in-hand.

Indeed, Lammy and Healey appear to find inspiration in Bevin. Writing in the Daily Telegraph in April, they declared:

Seventy-five years ago today, the great Labour foreign secretary, Ernest Bevin, signed the North Atlantic Treaty in Washington DC. Out of the ashes of the Second World War, we came together with our allies in defence of peace. No single act has done more to protect Britain’s – or Europe’s – security in the years since.

A month later, Lammy invoked Bevin as his guide (alongside Robin Cook) in an article for Foreign Affairs entitled ‘The case for progressive realism’.

Implications

That Lammy and Healey look to Bevin is praiseworthy because he is widely seen as the most successful British foreign secretary of the 20th century, if not all time. But it is still unclear how a progressive realist approach will add value to existing policy.

That Labour has embraced the need to contain Russia and assist Ukraine, shore up NATO, and work with new allies and partners, such as Japan and Australia, as well as emerging countries in the so-called ‘middle ground’, is not particularly innovative – it simply follows the previous government’s approach. Nor is Starmer’s commitment to spend 2.5% of GDP on defence and modernise British strategic nuclear forces, which are established policies.

Where Labour may differ is by doubling down on stopping Russia and helping Ukraine, drawing the EU closer to the UK, and embracing a more forceful policy in relation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). It may also place greater emphasis on human rights and foreign aid, especially in Africa. At the very least, the new government has committed to undertake an audit of British engagement with the PRC within the first 100 days of taking office, as well as a Strategic Defence Review within the first year.

Healey and Lammy: Key interventions in opposition

Speeches:

Lammy’s speech to the Institute for Government (17/05/2024)

Healey’s speech to Policy Exchange (28/02/2024)

Lammy’s speech to the Fabian Society (01/02/2024)

Healey and Lammy in conversation at the Wilson Centre (22/09/2023)

Healey’s speech to the Royal United Services Institute (07/02/2023)

Articles:

If you found this Cable useful, please subscribe or pledge your support!

What do you think about this Cable? Why not leave a comment below?

Really useful round-up. I’m very sceptical about Lammy but I think Healey is on the whole more sound (notwithstanding my doubts about a “security pact” with the EU).